PORTLAND, Ore. — In Oregon, there are two ways that a person with severe mental illness can be compelled to get treatment and care.

The first path is through a process called "civil commitment" — where doctors and a judge can order involuntary treatment if they find a person to be a danger to themselves or others, at imminent risk.

The second path is through the criminal justice system. A person may commit a crime, get arrested, and is then evaluated and transferred from a jail to a facility like the Oregon State Hospital for mandatory treatment and potential restoration if they're deemed unable to aid and assist in their own defense.

Over the last five years, the "civil" route — the preventative care route — has all but vanished in Oregon.

“The system is failing to actually treat people within the non-criminal part of the system, making them easily criminalized,” said Lisa Dailey, executive director of the nonprofit Treatment Advocacy Center, which studies state-by-state commitment laws. “(Oregon) is going in the wrong direction.”

And with treatment of acute mental illness left to local institutions, four of the state's largest hospital systems are suing the Oregon Health Authority over the "neglect" of civil commitment patients.

Dwindling beds and orders of the court

Nationally, the number of state psychiatric hospital beds has been declining for decades, and in the last 15 years, the proportion of beds occupied by criminal patients has outpaced the percentage of beds occupied by civil patients, according to TAC.

The change is reflective of a system that waits for people with severe mental illness to commit a crime before mandating treatment — and perhaps nowhere in the country is that switch more evident than in Oregon.

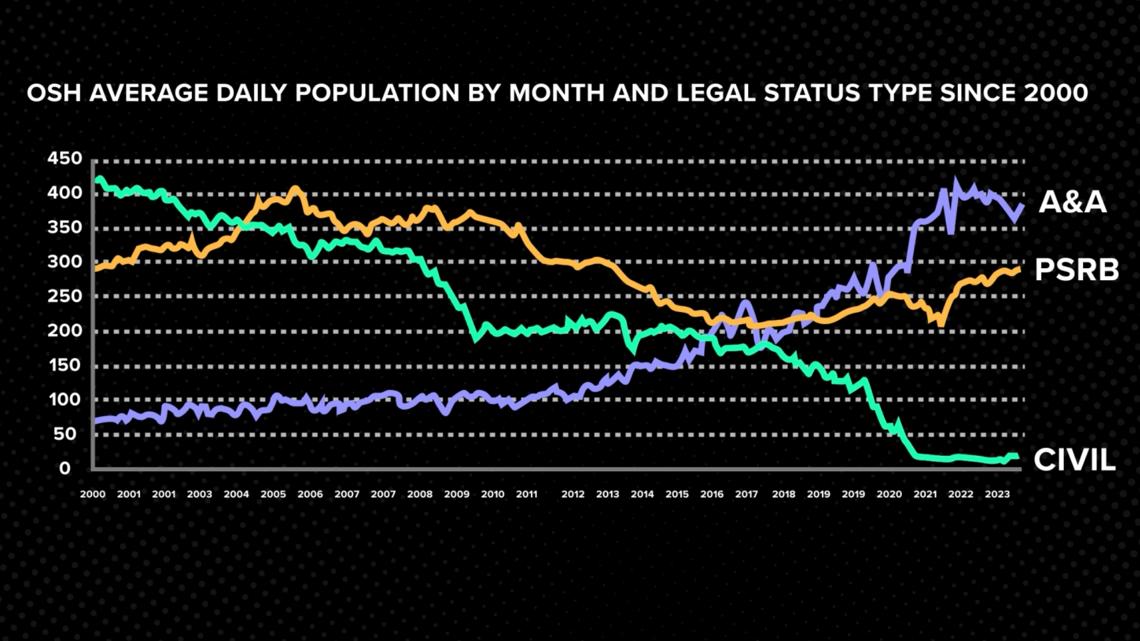

As recently as 2018, the Oregon State Hospital reported a fairly even split of care among its three primary patient types, including civil commitment, aid and assist, and psychiatric security review board. The last refers to people who have been found guilty of a crime "except for insanity" and committed to the custody of the state, instead of those awaiting trial.

However, people in jail with severe mental illness — the aid and assist patients — were waiting too long for care and transportation, breaking national standards.

In 2019, a judge ordered the Oregon Health Authority to comply with a federal order and take jailed patients with severe mental illness to the state hospital within seven days.

Compelled by that court order, OHA started prioritizing criminal justice cases, significantly decreasing the amount of civil patients it would admit in order to open up bed space.

RELATED: Court rulings demand Oregon State Hospital toe the line between patients' rights and public safety

By 2021, civil commitment in Oregon was nearly extinct. As a result, long-term mental health care is frequently only available to someone who has committed a serious crime.

'Just getting further into a hole'

Beyond the bounds of state custody, people with severe mental illness are often cycled in and out of acute care hospitals and community-based options that are ill-equipped to provide lasting treatment — leading to a dangerous waiting game.

“They’ve been abandoned by the state, and they’ve been forgotten about,” said Melissa Eckstein, president of the Unity Center for Behavioral Health, a go-to source for mental health treatment in Portland.

Eckstein told KGW that Unity used to send about 400 people a year to the state hospital for treatment. Now, with admission priority given to criminal patients, Unity sends "just a handful" each year.

“Our treatment team is really put into a challenging situation because the things that they believe will help that person have the most fulfilling life and be able to stay stable, they're not available to them,” Eckstein said.

When asked if there’s an option that’s not the Oregon State Hospital where Unity could transfer these types of civil patients, Eckstein responded: “Right now, there’s really not.”

KGW has shared stories of people and family members looking for answers within the system.

Eric Gardner’s family said that Eric is now homeless after he couldn’t be forced into care. Kenny Benton couldn’t recognize his own illness, only getting treatment after threatening his mom with a knife. And Brett Meister was civilly committed four times but failed to get step-down help after each release.

In 2023, the Oregon State Hospital admitted 1,209 patients on orders for treatment and restoration so that they could aid and assist with their own pending criminal case, according to OHA. The hospital admitted just 15 civil commitment patients that year.

“It feels like every month that passes, we’re just getting further into a hole,” Eckstein said.

Without a place to go, patients with severe mental illness are “taking up very vital and limited community-based hospital beds,” according to Eckstein.

In response, four of Oregon’s largest hospital groups — Legacy (which includes Unity), Providence, PeaceHealth and St. Charles — are suing the OHA, saying the state has failed to care for severely mentally ill people by neglecting civil commitments and instead "warehousing people" in acute care hospitals.

A federal judge ruled against the hospital systems and they’re appealing that decision, with a hearing set for May 8.

Last in the nation

When compared to other states on civil commitment standards and admissions, Oregon increasingly stands alone.

A Treatment Advocacy Center study found Oregon uses 7% of its available state mental health care bed space on civil cases, instead of criminal. That ranked last in the country out of any state that allows for civil commitment. The national average for civil patient occupancy is 48%, according to TAC.

“You are essentially creating a system where the only time that people receive care it's in the most expensive, costly and least effective setting,” said Dailey.

Dailey told KGW that society wouldn’t tolerate this system of crime-before-care for any other type of health care, asking why should we with mental illness?

“You're creating a system where care is predicated on the idea that there has to be a victim,” Dailey said. “I don’t think that makes any sense and I don’t think most people would agree that they want that.”

Washington County District Attorney Kevin Barton told KGW that Oregon's civil commitment process is "broken," saying the standards are so high it forces the justice system to step in as a system of last resort.

"That often is the only pathway someone has toward some level of mental health treatment, and that is an absurd way of approaching this issue," Barton said.

Barton said all levels of government and health care believe there is a serious problem, but there's been little motivation to make sweeping changes.

"There's a lack of political will and a lack of leadership to actually address the problem," he said. "Instead, we have work group after work group ... but nothing actually happens to fix it, and I find it incredibly frustrating."

This is part two of a three-part KGW "Uncommitted" series exploring how Oregon has effectively criminalized severe mental illness over the past five years, often waiting for individuals to commit a serious crime before mandating treatment. The reports will air at 6:30 p.m. during KGW’s The Story broadcast this week.