HOOD RIVER, Ore. — Portland-area drivers were likely sighing in relief earlier this year when Gov. Tina Kotek ordered a pause on all new tolling in Oregon until 2026, but the order does not apply to tolls that are already in place — and one of those sets of tolls is about to go up.

The Port of Hood River Commission voted last week to raise tolls on the Hood River-White Salmon Interstate Bridge, the sole crossing linking the two cities across the Columbia River. It's a pretty big hike — from $2 per car to $3.50 for drivers paying cash, and from $1 per car to $1.75 with the automatic payment system.

But there's a good reason for the higher fare. The long-running effort to replace the Interstate Bridge in Portland tends to be the first thing people think of when it comes to Columbia River bridges that need updating, but the Hood River Bridge will turn 100 years old next year, and it's definitely showing its age. Local officials say it's past time for a replacement, and the toll increase is going to help make that happen, starting in just a couple years.

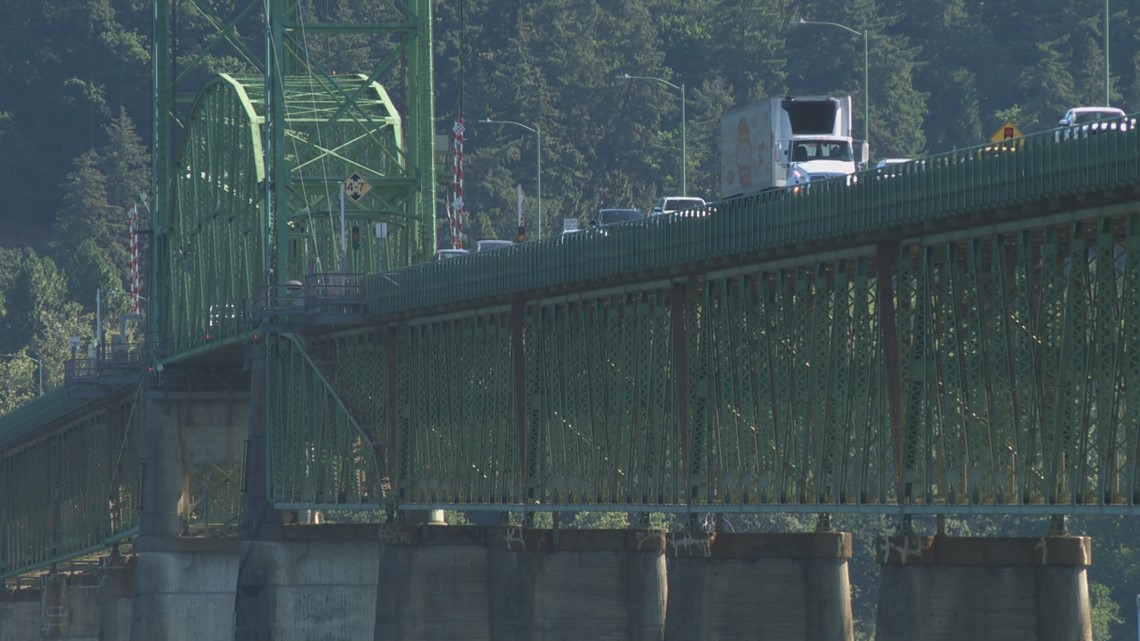

Aging, narrow structure

When the Hood River Bridge opened in 1924, the baseline vehicle toll was 75 cents, with higher tolls for bigger loads — but instead of step increases based on the number of additional axles on the vehicle, the tolls went up based on the number of additional animals pulling it, according to the Port of Hood River website.

"The original bridge had a wooden deck, and it had the old Model Ts. It was a different world back in the 1920s," said Kevin Greenwood, executive director of the Port of Hood River.

The port bought the bridge from its original private owners in 1950, and has maintained it ever since. It's received some big upgrades over its life, including a major project to raise it and add a lift span in 1938 and a seismic retrofit to strengthen it in the 1990s — although it's still not expected to fare as well as a modern bridge would when the Big One hits.

And there are many deficiencies that no retrofit can solve, such as the fact that the support columns are spaced uncomfortably close together, leaving barges on the main Columbia River channel with little room for error as they thread their way through.

Width is also a big problem up on the bridge deck, where traffic moves in two narrow lanes with no shoulders. It's so cramped that drivers in big vehicles are sometimes urged to fold in their mirrors to make sure they don't get sheared off. And if two big vehicles aren't careful when passing, the result can be even worse.

"We actually have trucks, fruit trucks and lumber trucks, lock up mid-span," Greenwood said. "That causes huge traffic problems, all the way back onto Highway 14 and I-84."

No shoulders on the bridge means there's no turnaround space, he said, so all the cars on the bridge have to back all the way out to whichever end they can reach so crews can get in and untangle the trucks. Even when traffic is moving smoothly, the claustrophobic lanes and high winds can make for a harrowing drive despite the bridge's 15 mph speed limit.

"You can really feel your car moving on that steel deck, and so that really makes it dicey ... if you're not a real confident driver," Greenwood said. "There's a lot of people that only drive this bridge once, because they just don't feel safe doing it."

'Neighborhood connector'

Avoiding the bridge isn't an option for local residents, especially those on the north side of the river. A majority of the bridge's 4 million annual crossings are drivers coming from Bingen and White Salmon and commuting to the larger city of Hood River, and the closest alternative crossing posts are both more than 20 miles away in either direction.

"This new bridge really is essential to the long-term resiliency of our Washington communities in west Klickitat (County)," said White Salmon Mayor Marla Keethler. "This really is our lifeline ... childcare, a lot of medical services, daily grocery runs, this bridge becomes that neighborhood connector, more or less."

Keethler is also one of the commissioners on the newly-created Hood River-White Salmon Bridge Authority, which officially took over management of the bridge replacement project July 1 and will own and operate the new bridge when it's done. The Port of Hood River will continue to play a supporting role, but Keethler said the new authority's shared leadership structure was an important change for Washington residents.

"It allows bi-state representation, and going forward ensures that all tolls on that new bridge stay only with that bridge, for the long-term operation and maintenance of that singular facility," she said, "and I think that's been a key part, especially for Washington residents, is to finally have a seat at the table and make sure that there's representation long term."

The new bridge authority grew out of a bi-state working group that began meeting about five years ago, and officials said that development marked a turning point in the quest to bring the long-simmering idea of a new crossing into reality.

"The great thing is that we're all on the same team," said Kristi Chapman, president of the Port of Hood River Commission. "And so we have support from the Washington side, we have support from the Oregon side, and we're working with the Native American tribes, which has been starting to become very successful. So it seems like everyone is all on the same page, that this is a beautiful bridge, but it's not functional anymore."

Replacement design and cost

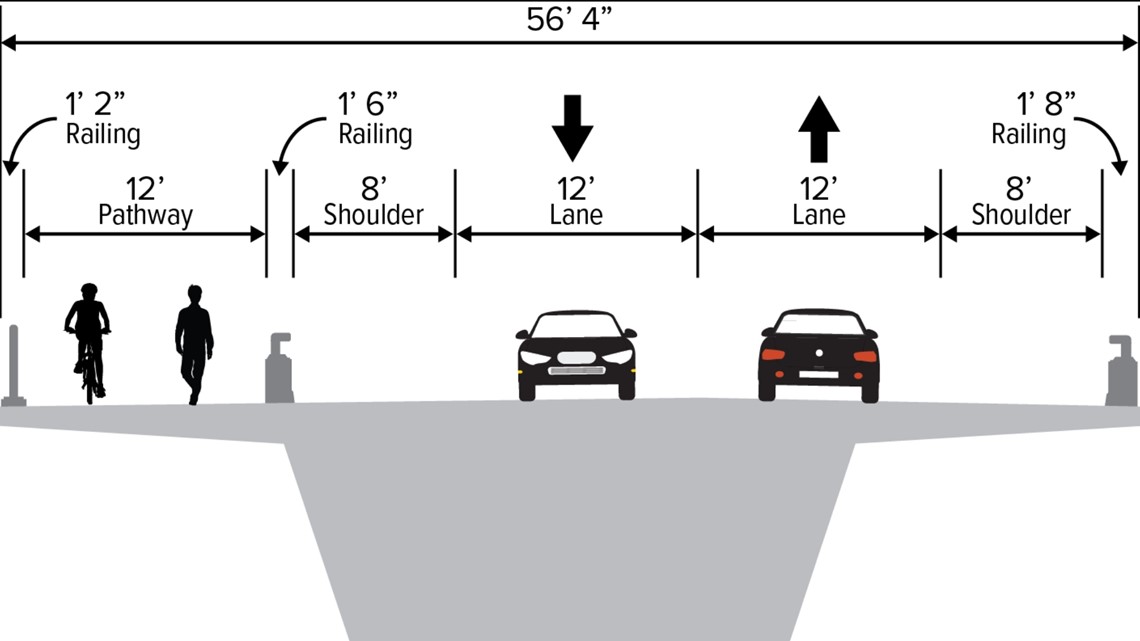

The replacement crossing is still going through the federal environmental review process, so the design isn't 100% complete, but the big pieces are already locked in place. Like its predecessor, it will be a two-lane bridge, but it'll be more than twice as wide, with 12-foot lanes and 8-foot shoulders.

It'll also have a multi-modal path on the western side for bike and pedestrian access — something the current bridge lacks entirely.

The deck will be concrete rather than steel grating, and there won't be a lift span — the new bridge will cross the main river channel at 90 feet, high enough to provide clearance for all vessels that travel as far up the Columbia as Hood River.

The project has secured about $118 million in funding so far, according to its website, but there's still a lot more that will need to be lined up in the next two years before construction can begin.

"The overall cost to complete is about $600 million," Chapman said, "so the goal is if we could get a commitment from Oregon and Washington of about $125 million apiece, and then our commitment is this $15-20 million for the Local Community Reserve Fund that would help us get a (Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act) or other fund federal funding that could then push us over that $525-600 million and get us to where we need to go."

The $15-20 million is the additional revenue that the upcoming toll hike on the current bridge is expected to bring in. If all the other financial pieces come together, the planners hope construction can get underway in late 2025 or early 2026.

The new bridge will be build slightly to the west of the existing one and is tentatively planned to open in 2029. Once traffic shifts over to the new bridge, the old one will be decommissioned and removed after standing for just over a century.

The tolling question

You might be wondering why a century-old bridge has tolls in the first place. After all, the Astoria and Interstate bridges both had tolls once upon a time, but they ended once construction costs were paid off.

The difference, Greenwood explained, is that those bridges are owned by the Oregon and Washington Departments of Transportation, which can use state gas tax revenue to pay for maintenance. The Hood River Bridge is owned by the port, which doesn’t have access to that funding, so they have to take a more direct approach to cover maintenance costs. That’s also why the Bridge of the Gods has tolls — it’s owned by the Port of Cascade Locks.

The new bi-state bridge authority will have the same limitation, which means the current Hood River Bridge's tolls are going to transfer over to the replacement, and they'll remain a permanent feature of the new bridge as well. But port staff said the toll hike coming up in September is the only one they think they'll need to make during the remaining design and construction period.