GOLDENDALE, Wash. — Looking at the windswept bluffs of the eastern Columbia River Gorge, Jeremy Takala can’t help but reflect on his people’s connection to the land.

“The Columbia River, as my aunt would say, is the veins of Mother Earth,” said Takala, an elected member of the Yakama Nation tribal council. “It's like us. The blood of who we are and the blood of Mother Earth flows here.”

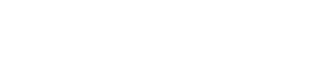

Citizens of Yakama Nation, made up of 14 bands and tribes in eastern Washington, still practice their traditional ways in this part of the state, gathering food and medicine that grows along the basalt cliffs and pulling salmon from the Columbia.

“Every year we honor our foods when they come around within our home. Many of our elders, the adults, the children, partake and still continue that way of life,” Takala said. “With the project being proposed here, it will definitely impact our life.”

Takala was referring to a pumped hydroelectric energy storage project being proposed south of Goldendale, Washington. The project’s backers tout the clean energy potential of the system and say it’s a necessary supplement to the Northwest’s energy grid if Oregon and Washington are to meet their ambitious climate goals.

For Takala and Elaine Harvey, another citizen of Yakama Nation, the proposal is just the most recent in a string of infrastructure projects that downplay or ignore the concerns of the people who have been on the land the longest.

“This just feels like we are going through the times when the dams were constructed,” Harvey said. “When the government decided they're going to do this, and they did it no matter what the impacts to the tribes were.”

How it would work

The technology behind pumped hydro energy storage is not new. Erik Steimle with Rye Development, the company behind the proposal, explained.

“Pumped hydro storage is the oldest form, it's also the most used form of energy storage in the U.S.,” he said.

The proposal near Goldendale would see the construction of two 60-acre reservoirs. The lower reservoir would be on the site of a former aluminum smelting plant next to the Columbia River near the John Day Dam. More than 2,000 feet above, perched on a ridgetop to the north, would be the upper reservoir. A 30-foot diameter tunnel, fitted with a turbine, would connect the two.

One of the biggest problems with wind and solar power is their inconsistency. They produce lots of power on sunny days and when the wind is blowing, but those conditions don’t always line up with peak demand for electricity.

Pumped hydro storage solves that problem.

When wind and solar systems produce more energy than can be used, that electricity is used to pump water from the lower reservoir into the upper.

When the wind is calm or the sun isn’t shining, the water is released from the upper reservoir through the tunnel, spinning the turbine, “and we have on-demand, carbon-free electricity,” Steimle said.

The system is a “closed loop,” meaning it would only need to be filled once and then topped off annually to make up for seepage and water loss from evaporation.

Energy storage will become increasingly important as Oregon and Washington work toward ambitious clean energy goals. Oregon has set 2040 as its goal to reach 100% carbon-free electricity production. Washington has the same goal five years later.

To get there, Steimle pointed to studies saying that the region will need between 5,000 and 10,000 megawatts of energy storage capacity. The pumped hydro project near Goldendale would be capable of producing 1,200 megawatts, enough to power the city of Seattle for up to 12 hours.

Some of that could come from lithium-ion batteries, Steimle said, but that kind of energy storage comes with drawbacks.

Pumped hydro “actually takes some of the stress off raw materials, the foreign pipeline, all that stuff that is going into support lithium-ion batteries and providing a little diversity,” Steimle said. “For ratepayers in Portland, lithium-ion batteries may be great for certain portions of the grid, but they are something we have to throw out and pay for every 15 years.”

The site for the project was chosen for a number of reasons, Steimle said. It’s on private land that’s already been developed; the site of the lower reservoir was a smelting plant and the ridge above is home to a wind farm. It’s also close to existing transmission lines and the geography of the area is well suited for a pumped hydro system.

“I see this as a project that this is a wise use of an existing piece of private land where we don't have to build new transmission lines. We don't have to build new roads,” Steimle said. “And it provides a meaningful amount of storage to the state as an alternative to building valleys of lithium-ion battery warehouses.”

The $2 billion project would also bring 3,000 temporary construction jobs to Kilickitat County and up to $14 million in annual tax revenue.

For all the problems the project can solve, though, it creates just as many for the people of Yakama Nation.

‘We’re basically seeing history repeat itself’

The land where Rye Development wants to build the project is home to several sites significant to the people of Yakama Nation.

The most at risk, though, is an area called Juniper Point, or Pushpum in the Yakama language.

The highest peak for miles around, Pushpum has been sacred to tribes in the area for as long as they’ve been there, both as part of their legends and as an important place for gathering.

“This project here will devastate these rock formations and our foods and our medicine,” Takala said, noting that tribes along the Columbia have seen their important sites destroyed before. “We're basically seeing history repeat itself.”

As the dams went up along the Columbia – both to produce electricity and to facilitate freight travel – numerous villages, burial sites and petroglyphs were inundated, including Harvey’s ancestral village near what is now Maryhill, Washington, west of the John Day Dam.

One of the most important sites lost when the dams went up was Celilo Falls, a series of rapids on the Columbia where Indigenous people had fished for centuries. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers provided compensation for the loss of the fishing site, but there was something invaluable lost when the villages and cultural sites were flooded.

Harvey said the pumped hydro storage proposal feels similar.

“It's like the tribes continue to carry the burden for what everyone is calling green energy.”

Now she’s afraid that burden may fall upon Pushpum.

“It is known as the mother of all roots,” Harvey said. “This place is very important because it holds the seeds. The culturally significant seeds of the roots and berries. Those resources that we feel are very, very significant to us.”

Steimle said Rye Development understands the tribes’ concerns.

“We understand that this area is significant,” he said. “It doesn't matter so much that it's private land or that it's fully developed, there's still significance to the site.”

To mitigate the impact to Pushpum and other important cultural sites in the area, the company has moved the proposed site of the upper reservoir back from the ridgetop. They also plan to develop a “historic properties management plan” that would call for construction to cease if workers come upon any cultural relevant sites during excavation.

“Part of what we can do is continue to have conversation and provide access to traditional gathering and other types of activities,” Steimle said.

Takala and Harvey aren’t interested in the company's mitigation efforts, though.

“I don't think there's any mitigation that would mitigate losing the sacred site,” Harvey said. “They want to drill a 30-foot tunnel with a powerhouse in it. That's a total desecration.”

A question of communication

From Takala and Harvey’s perspective, projects like this one should require consent from the tribes, not just consultation.

In 1855, the tribes signed a treaty relinquishing much of their land in and establishing a reservation north of Goldendale. The treaty retained fishing, hunting and gathering rights on much of eastern Washington, however, on what are now known as “ceded lands.”

“Free prior consent, that's a huge thing for us. If we say no then that has to be accepted,” Takala said. “We are not a public stakeholder. We are a sovereign nation.”

Harvey said it often feels like, when these types of projects are proposed, the tribes aren’t even made aware until late in the process.

“They spend a year or two on their studies and throw us the (Environmental Impact Study) and say, ‘Well, what do you think about this project?’ and give us a 30-day response?” she said. “That's not fair to the tribes.”

The problem comes down to a fundamental difference in how Yakama Nation views the land as opposed to how it’s viewed by developers, Takala said. Developers look at the land and think "what can this do for us," whereas Takala looks at the mountains, rivers and canyons and sees parts of nature that are fulfilling their purpose just by existing.

“I understand the developer is not from this area, who has no knowledge or no respect to what the tribes hold to their heart here,” he said. “So for someone to come in from the east side or another country is, in my heart and to us, it's very disrespectful.”

What Takala and Harvey are hoping for is direct talks with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission on a nation-to-nation basis. Yakama Nation has sent letters to the commission asking for meetings and received no response. KGW asked the commission whether it would be engaging with the tribes and also did not hear back.

Takala stressed that Yakama Nation is not against renewable energy.

“I know to the public eye or to many developers, they always say ‘well the tribes are always against this or against that,’” he said. “The tribes are not against alternative energy. What we are concerned about is where these projects are being proposed.”

The commission is set to release its final Environmental Impact Statement later this year.

If the statement is approved, the last hurdle before construction can get underway will be a 50-year license for construction and operation. If that license is issued, Steimle said the project could be fully operational by 2028.