![4-1-2016 roger penske [image : 82518836]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/media/2016/04/01/USATODAY/USATODAY/635951146693480001-USP-NASCAR--Daytona-500-Practice.jpg)

![What to watch for at Martinsville Speedway [video : 82426486]](http://videos.usatoday.net/Brightcove2/29906170001/2016/03/29906170001_4823248525001_4823243919001-vs.jpg?pubId=29906170001)

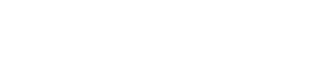

Roger Penske’s 50 years in motorsports ownership has been resplendent with success: a record 16 wins in the Indianapolis 500, two Daytona 500 victories and 28 national championships.

A billionaire businessman who employs roughly 55,000 globally in a variegated business empire, he underpins his business philosophy with the notion that progress can only be made by “leading from the front,” a bit of board room speak often repeated by those he employs.

But there have been moments difficult to glance away from in a resumption of forward scan. Penske often references them unprompted, as if to remind himself that hesitation is stagnation. Or in the most recent example, that ultimate planning and execution ultimately yield nothing.

“What I really remember are the two worst situations,” Penske told USA TODAY Sports. “One was in 1995, where we didn’t qualify for ‘the race’. The second was at Martinsville last year when (Matt) Kenseth knocked Joey (Logano) out. Just … bizarre.”

‘The race’ was the 1995 Indianapolis 500, where Al Unser Jr. became the first defending winner not to qualify. Nor did Emerson Fittipaldi, after he and Unser Jr. combined to lead 193 of 200 laps the previous May. Penske regrouped but still reflects on the failure for what value can be gleaned from it.

![Gluck: Promoting Kenseth-Logano crash exemplifies NASCAR's dilemma [oembed : 82518888] [oembed : 82518888] [oembed : 82518888] [oembed : 82518888] [oembed : 82518888] [oembed : 82518888] [oembed : 82518888] [oembed : 82518888] [oembed : 82518888] [oembed : 82518888]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/smartembed.png)

The other one, though, is tougher to grasp. Penske returns to the scene of that other great organizational heartbreak on Sunday as the Sprint Cup series reconvenes at Martinsville Speedway for the first time since Logano’s seemingly inexorable march to victory and a chance at a championship was undone in an act of retaliation by driver Kenseth.

Logano led with 45 laps remaining last fall – he’d paced 207 of 455 and was cruising to what would have been a fourth consecutive Chase for the Sprint Cup victory – when the lapped Kenseth stalked and wrecked him in Turn 1. Kenseth and Logano had sparred verbally since the fifth race of the Chase when Logano bumped Kenseth off the lead at Kansas Speedway to claim a win. Kenseth, who was eliminated from the Chase a week later, questioned Logano’s ethics and tactics and after the Martinsville incident was suspended – following two levels of appeal – for two races. Logano, his momentum quelled, failed to qualify for the championship final at Homestead-Miami Speedway and finished sixth in points.

Penske was disgusted, but left Martinsville as the race wound through its final laps. He informed Logano through his lieutenants that there would be no retribution although the packed Martinsville garage area bristled with anticipation of violence in the heightened anxiety of the Chase. Logano’s crew labored to make the crippled No. 22 Ford race-worthy again as Kenseth was parked by NASCAR. Logano deemed Kenseth’s play a “coward” move but otherwise symbolized the uneasy restraint of his team.

![Kenseth wrecks Logano [oembed : 82518996] [oembed : 82518996] [oembed : 82518996] [oembed : 82518996] [oembed : 82518996] [oembed : 82518996] [oembed : 82518996] [oembed : 82518996] [oembed : 82518996] [oembed : 82518996]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/smartembed.png)

Penske was the first to the helipad near the track and watched Martinsville disappear behind him as a landmark in disappointment.

“I didn’t want to talk to anybody,” he said, “because I might have done exactly what I told everyone else not to do.”

As a wildly popular victory by Jeff Gordon was feted on the celebration stage after the race, Logano walked a darkened pit road with team president Tim Cindric, the driver brandishing the face-consuming grin that has become his unwitting hallmark.

“There’s nothing you going to change there,” Cindric said. “There’s nothing you can expect NASCAR or anybody else to do to change our fate. I think our approach sometimes … it isn’t because we don’t care or you’re complacent about anything. We have as much passion as anybody does, but there’s a point where there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Said Logano: ““I’m proud of the way we handled things.”

PHOTOS: In the driver's seat with Joey Logano

![Joey Logano through the years [gallery : 2774503]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/c127ffc90bfee1d38387d8eae09e9dc729507220/c=0-0-3763-3216/local/-/media/USATODAY/USATODAY/2013/09/06/1378446753002-GTY-172749058.jpg)

The experience, in its raw real time, conjured similar pangs of disappointment of 1995 for Penske. Penske had won seven of the previous 11 installments of the race he most covets, with Unser dominating in 1994 with a Mercedes-Benz 500I pushrod engine that was legislated moot by rules changes that sapped its horsepower advantage and revealed handling problems the next season. In a post-race press conference in 1995, Penske said that his team “didn't come prepared” and set about making sure that never happened again.

“First I had to put my arms around Unser and Fittipaldi in 1995,” Penske said. “I remember walking back to the garage, qualifying’s over and we’re not even in the race, but we went on and we’re fine.”

There was no engine formula to analyze after Martinsville, though, no aerodynamics package to hone. There was just a radical variable he could not control, a disconcerting prospect for the businessman and the racer.

“I just remember getting ahold of [vice president of marketing and communications] Jonathan [Gibson] and I said, ‘Just tell Joey he just has to keep his cool. Anything he says, it’s not going to be good,' ” Penske said. “It was about damage control after it happened and then the accident situation sunk in.”

Sitting at a desk in the office of his IndyCar transporter, his fingertips forming a triangle before his face, Penske has moved on from disgust but still seems aghast at the scenario that played out in his last trip to Martinsville.

“There’s nothing you can do about it. When you think about it…. of all the things I think about, we’ve run out of gas on the last lap, we got wrecked on the last lap, those are two that will go down as probably the toughest situations,” he said.

But perhaps remembering his own ethos, he thrust his hands forward before making a point. It was as if he’d concocted a plan or a directive to insulate his team from such a disappointment in the future.

“But the good news,” he said, “is we just continue on and try to do better.”

Follow James on Twitter @brantjames

![Fontana: Jimmie Johnson's super triumph by Start Your Engines [oembed : 82519040] [oembed : 82519040] [oembed : 82519040] [oembed : 82519040] [oembed : 82519040] [oembed : 82519040] [oembed : 82519040] [oembed : 82519040] [oembed : 82519040] [oembed : 82519040]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/smartembed.png)