SALEM, Ore. — As Oregon continues to grapple with a shortage of public defenders, it's also making changes that may make it easier for aspiring attorneys to begin practicing. After a unanimous decision this week at the Oregon Supreme Court, the bar exam will no longer be the only way for law school graduates to become licensed.

Beginning in May of next year, a program called the "Supervised Practice Portfolio Examination" will become accessible to aspiring attorneys. Law school graduates who choose to go that route will be able to practice in Oregon without taking the bar exam. Instead, they'll have to prove themselves on the job.

Requirements include 675 hours of practice under the supervision of a licensed Oregon attorney. That number was not plucked out at random, but represents that general amount of time someone would otherwise spend studying for the bar exam.

Next, they'll have to submit a portfolio of their work, comprised of eight different projects, to the Oregon Board of Bar Examiners, which will give them either a thumbs-up or thumbs-down grade, not unlike grading for the bar exam.

But it's also a big departure from the traditional bar exam, which has a time-honored reputation as a particularly grueling test. Data shows that around 40% of people who take the bar exam fail.

Much of the initial reaction to this change — sometimes framed in response to headlines suggesting that Oregon is simply removing the bar exam requirement — has been about what you might expect. Some people have already complained that it's yet another example of Oregon softening the rules and lowering standards, potentially letting unqualified people into the profession.

Is it lowering the bar?

The Story spoke to Brian Gallini, dean of Willamette University's College of Law, who helped craft this new program. He responded to those concerns with a simple question: Would you rather have a lawyer who can pass a test, or one who has already done hundreds of hours of the actual work that you expect them to do?

Gallini compared it to the rampant skepticism when Apple rolled out the iPhone, back when the BlackBerry was king.

"Everyone said, 'Oh, that's not going to go anywhere; I'm tied to my BlackBerry.' That was the phrase," he said. "But who has a BlackBerry anymore?"

He also compared the current process for lawyers to that of doctors or pilots, both of whom are required to complete hands-on training.

"If people really focused on what this current exam is doing, I think they'd be far more alarmed that they have the attorney who passed this, as opposed to the attorney who's going to be asked to do the sorts of things that the SPPE is going to ask candidates to do," Gallini said.

Gallini pointed to some big questions about the bar exam that have more recently come to light, particularly when it comes to equity. Data from the American Bar Association in 2021 showed that there is a 15% difference between white prospective lawyers passing the bar compared to law school graduates of color.

"Presumably we're testing minimum competence, but as it turns out, there is no evidence-based definition of minimum competence," Gallini said. "We're using multiple choice and essay questions that are closed book and timed ... No lawyer completes a multiple-choice question or completes a closed book, short answer essay in their practice."

And then there's the cost of the bar exam. Typically, Gallini said, courses to prep for the bar exam cost around $4,000, and that's after the cost of a law degree. It requires about six months of study, test-taking and waiting for results, possibly with little or no income to speak of, while the graduate needs to keep paying for their room and board, at the very least.

"Ask any graduate who has taken the bar exam whether they felt like the second they walked across the graduation stage they were ready to practice law, and the answer — overwhelmingly — is 'No,'" Gallini said. "And all of those things lead to one question, which is why are we doing it this way?"

A commitment to Oregon

The program that became the Supervised Practice Portfolio Examination took shape over the past three years, finally receiving approval from the Oregon Supreme Court on Tuesday. Once it begins in earnest next May, it will be open to all graduates across the country from schools accredited by the American Bar Association.

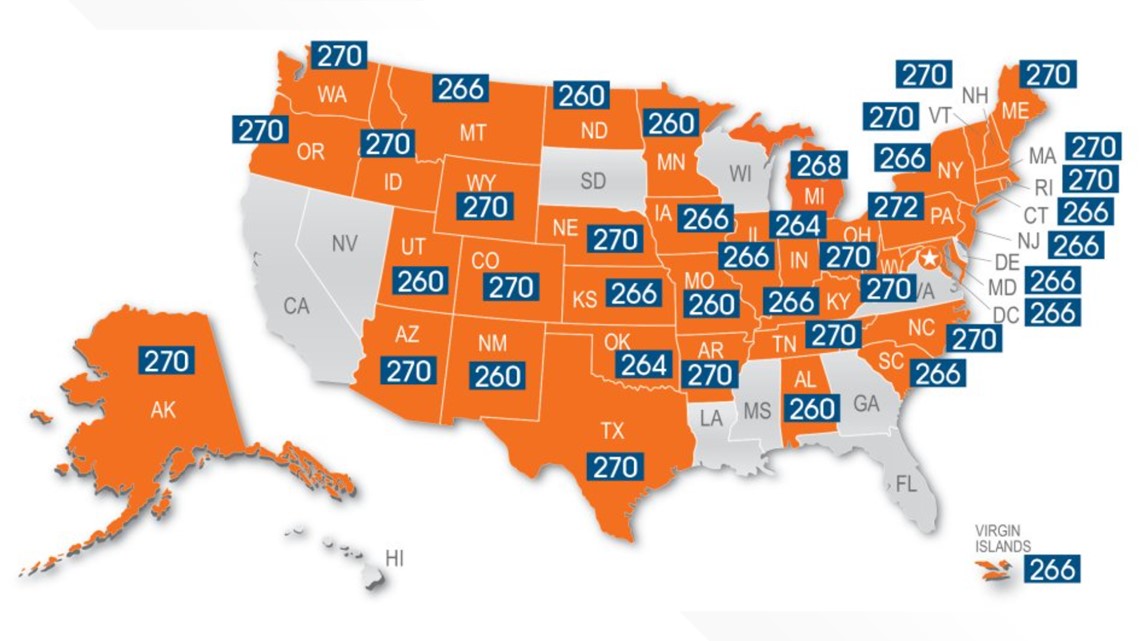

While that's a major achievement, the program has limitations. Graduates who go through this program instead of taking the bar exam will only be licensed to practice law in Oregon. Typically, people who pass the Uniform Bar Examination can practice in a number of different states depending on their score. The test is scored out of 400, and in Oregon and Washington the "cut score," as it's called, is 270.

The bar exam will still be there for Oregon's aspiring lawyers who prefer either the format or that ability to practice in other states, which could mean that the SPPE will be slow to draw in participants.

"I see a lot of students who want the flexibility that a portable license provides, and I think we've got some work to do to convince them that 'Hey, you should spend 675 hours,' as opposed to just 'You could bang this out in two days.' So I think we've got some work to do on that front," Gallini said.

What they hope to do is encourage students earlier in their law school experience to think about what they could do as attorneys in the state of Oregon in hopes of keeping that talent around.

While Oregon is the first state to implement something like the SPPE, Gallini said, several other states are already on the path to doing something similar. California will likely be next, and the state of Washington is looking at multiple pathways toward achieving a law license. Wisconsin and New Hampshire each have special licensing programs, while Maine, Nevada, Utah, North Dakota, Georgia and Minnesota are all considering licensure reforms.