SALEM, Ore. — Oregon will send free doses of naloxone, the medication that reverses opioid overdoses, to schools across the state. It's not a novel idea — Washington has been doing it for years — but the Oregon Health Authority's plan includes a concerning gap.

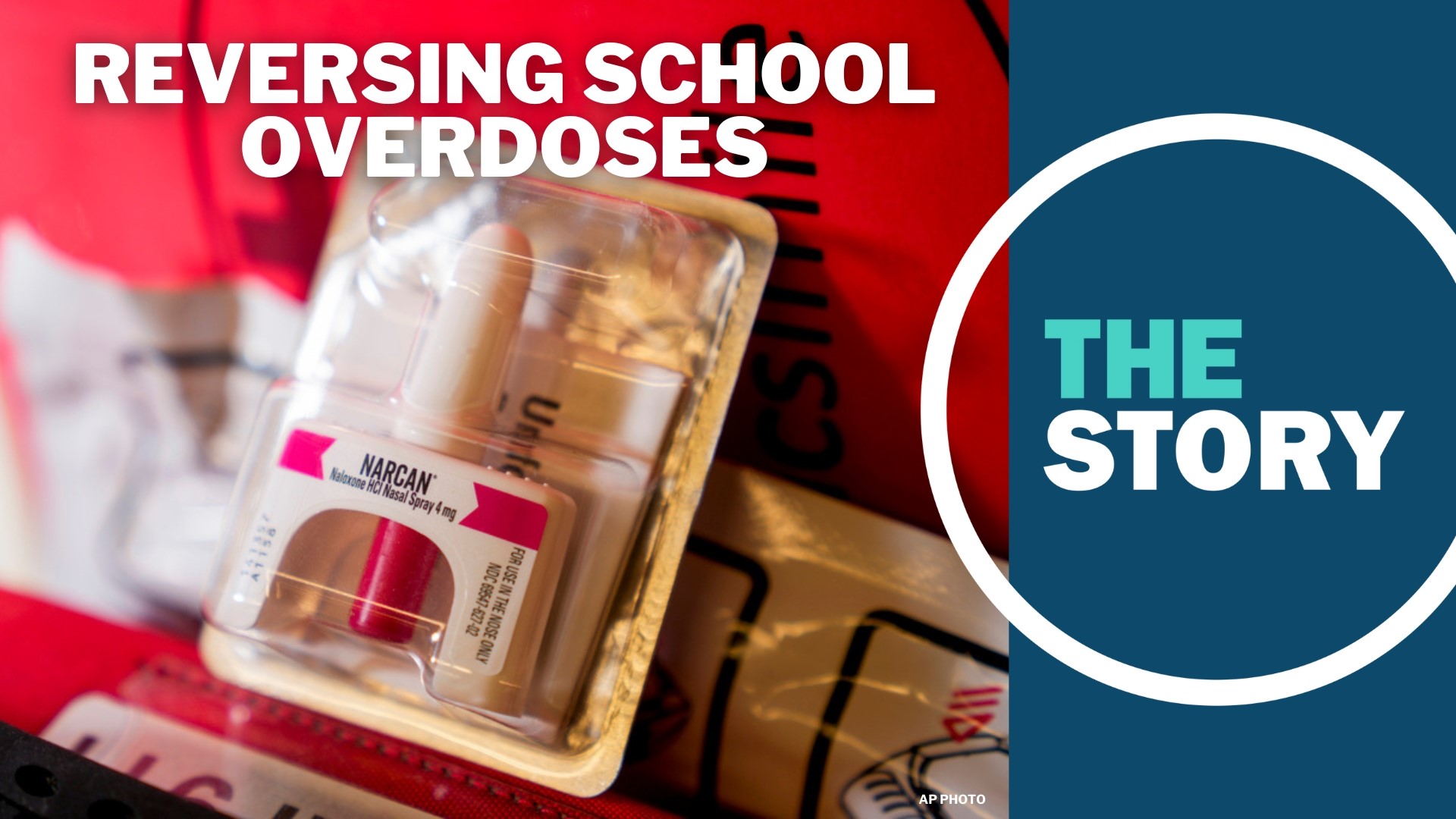

Naloxone, often bought under the brand name Narcan, is an easy-to-use nasal spray that can reverse an overdose. It’s championed as one of the "essential tools" to fight back against the escalating fentanyl crisis.

"Prevention is the most important thing here — preventing the overdose, making sure that people in schools have access in case a student does overdose on school property," said Tom Jeanne, deputy state health officer.

Jeanne said that more than 500 schools — from charter and private schools to public schools, community colleges, and universities — signed up for the free doses within a week of availability, demonstrating the high demand.

"It's been in the news. Everybody's aware of it," he said. "So even if a school or school district has not actually had any opioid overdoses in their schools, I think most of them are recognizing the need to be prepared."

RELATED: Parents of teen killed by fentanyl push for bill requiring fentanyl education in Oregon schools

The Oregon Health Authority will give each school up to three kits, each of which contains eight doses.

Health officials recommend putting naloxone near bathrooms, AEDs and first aid equipment, and on buses. Schools will ultimately decide where they put it.

But there’s a key element that’s missing from Oregon's plan. KGW asked the OHA how the state will know which schools are using naloxone, where and why they’re using it, and if they need replacements. The short answer: they won't.

"It's a good question. We don't have any reporting requirements in place right now," Jeanne said. "We're certainly going to be talking to schools and talking to the Department of Education to see how this rollout goes once the kits start, you know, hitting the ground in schools."

Without a reporting system, state officials could miss out on key information showing where the fentanyl crisis is growing, or which students are most at risk.

As it stands, the naloxone-to-schools plan is a one-time initiative. The state is using $693,000 from a $325 million settlement with opioid manufacturers and pharmaceutical distributors in order to fund the purchase and distribution of the nasal spray to schools.

Naloxone typically expires after three years.

"If we're getting to the point where schools are running out of naloxone, I think that's a really, you know, potentially bad situation to be in," Jeanne acknowledged. "And I think we need to reevaluate again. Thankfully, these overdoses on school property are very rare at this point. But even though the numbers are still small, the trends are not in the right direction right now."

Jeanne said the state plans to distribute the naloxone in two to three months, by early spring.

"I think ultimately, we would like to see the numbers of youth overdose deaths going down," he said. "And I think we will get there with the help of this naloxone, these naloxone kits."