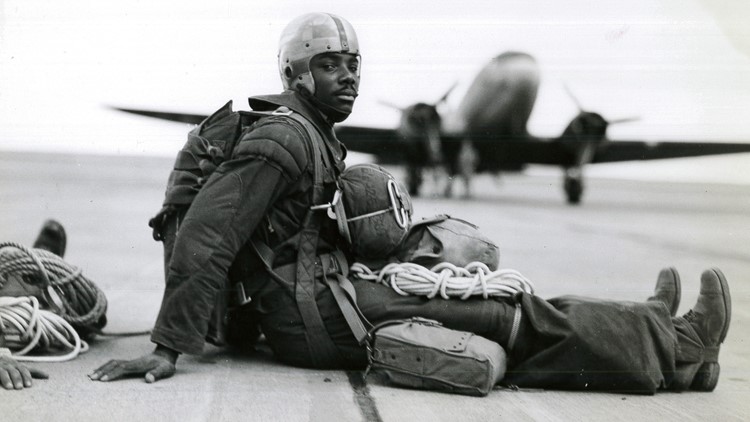

PORTLAND, Ore. — The 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, more commonly known as the "Triple Nickles," was the first all-Black paratrooper unit in U.S. history.

First organized in 1943 during World War II, the Triple Nickles trained at Fort Benning, Georgia, but were eventually transferred to Camp Mackall, North Carolina, to prepare for duty in Europe. At the time, the U.S. military was segregated and most Black soldiers were relegated to support roles, rarely trained as combat units let alone elite paratroopers.

For some in the unit, the prospect of fighting Hitler's army presented an exciting opportunity — a chance to prove that Black men were as brave and capable as their white counterparts.

But they were never sent to fight the Germans. By 1945, the Axis armies were in retreat and a new threat was developing in the American West — Japanese balloon bombs.

'Operation Firefly'

The battalion was sent to Pendleton, Oregon, on a secret mission even they knew nothing about — code-named "Operation Firefly."

Once in Oregon, the unit met members of the U.S. Forest Service. Only then did they learn what most Americans were unaware of. The Japanese had been launching balloon bombs into the jet stream that were landing, and exploding, across the United States.

“Their general orders then, and they didn’t know they had general orders, read: ‘the destruction of Japanese balloon bombs and the suppression of wildfires,'” said Dr. Bob Bartlett, a retired sociology professor and Army veteran who has studied the Triple Nickles for the last seven years.

With their orders now clear, the battalion became smokejumpers — the first military unit to do so — parachuting into densely wooded terrain, fighting fires and destroying enemy bombs.

“They didn’t know whether the fires were caused by lightning or careless campers, or a balloon bomb," Bartlett said. "So, when the fire call came they just knew we’re going."

And the Triple Nickles mission had become critical.

The Triple Nickles: America's first Black paratroopers

Just days before the unit arrived, six people were killed by a balloon bomb near Bly, Oregon, in Klamath County. Elsie Mitchell and five children died after a balloon they had discovered exploded. They were the only Americans in the continental United States to be killed by enemy fire during World War II.

Between 1944 and 1945, the Japanese launched an estimated 9,000 balloon bombs across the Pacific. Intent on burning forests and terrorizing the American public, the attacks ultimately failed. Only a few hundred balloons were ever found or seen in the United States and none of the widespread destruction ever occurred.

But the Triple Nickles remained committed to their mission. By the end of the 1945 fire season, the unit had participated in 36 fire missions with more than 1,200 individual jumps.

One of their own died that summer. Private First Class Malvin Brown, a medic, died after falling almost 150 feet from a tree while fighting a wildfire in the Umpqua National Forest. He was the first smokejumper to die in the line of duty.

Triple Nickles faced racial discrimination

Despite their bravery, the Triple Nickles, like other Black service members, faced discrimination in their own country.

Bartlett described an especially overt instance of racism he came across in his research. Prior to the unit's arrival in Pendleton, the town had only one USO club, an area where service members could socialize and recreate. After much deliberation, the Triple Nickles were invited to mingle with their fellow white comrades, said Bartlett. But hope for an integrated club was short lived.

"The white soldiers came in the front door, took one look, and went out the backdoor and said 'we're not doing it,'" Bartlett said.

Instead, a second USO club was established in Pendleton to serve the Black troops.

For the Triple Nickles, it was a reminder of their day-to-day reality: they were willing to risk their lives for a country that treated them as second-class citizens.

“They jumped into the fires of racism at the same time they were literally jumping into fire,” Bartlett said.

Due to the hard work of Professor Bartlett and others, the story of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion lives on.

A gesture of honor now officially marks the Triple Nickles' service on Main Street in Pendleton. It recognizes the first all-Black paratrooper battalion in American history — a group of men willing to defend our freedom, even as many continued to deny theirs.