PORTLAND, Ore. — At the center of the crisis on Portland's streets is a particularly stubborn knot, one gathered and cinched from the threads of homelessness, addiction and mental illness. And the professionals who treat the latter two will usually say that it's incredibly difficult to address one without simultaneously addressing all three.

In 2022, the Portland tri-county area conducted its federally mandated Point in Time Count of the local homeless population. The count found over 6,600 people experiencing homelessness, more than half of them unsheltered. Every year, the agencies that conduct this outreach acknowledge that it's probably an undercount.

Of the people interviewed, almost 36% self-reported having a mental health disorder and 35% reported having a substance use disorder. About 20% reported having both. Like the count itself, these numbers could also be higher than reported.

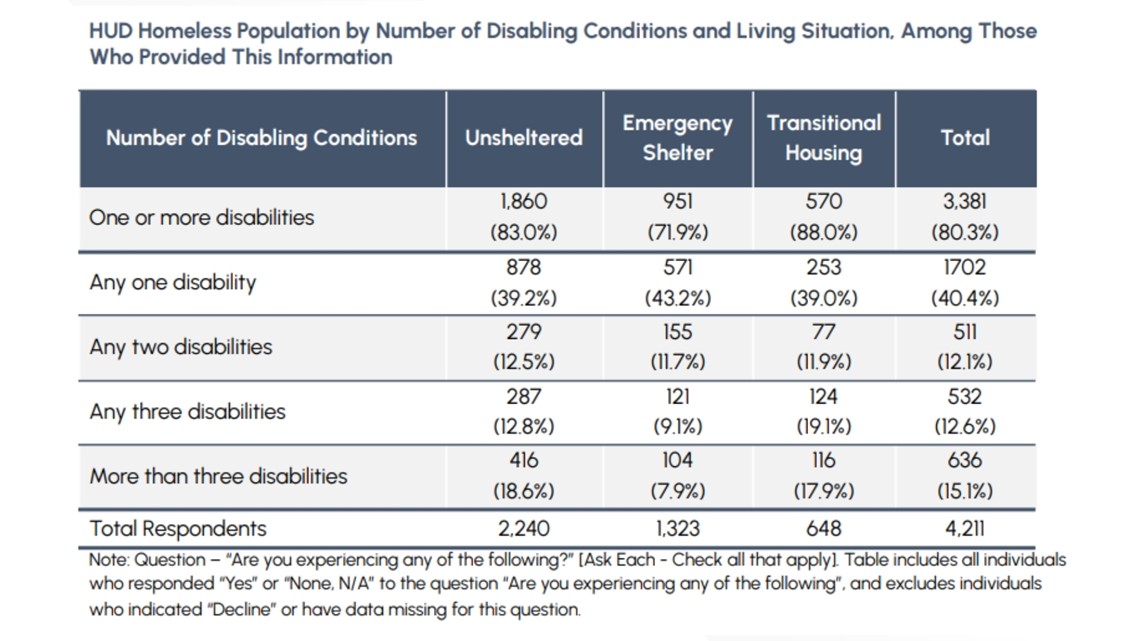

More than 80% of homeless people reported having at least one disability, of which mental illness and addiction were the two most common categories. Across the board, self-reported disabilities were higher among those living on the streets than people with some form of shelter.

The unseen world

Dr. Maureen Murphy-Ryan is in her fourth and final year as a resident in psychiatry at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. She's worked closely with clients who suffer from addiction and from severe mental illness, often without stable housing. Of particular interest to her are the acute symptoms of mental illness that often show up where those three meet — psychotic symptoms.

For her, the subject is both a professional and a personal one. She freely admits that, while already embarking on her career in psychiatric medicine, she was derailed for several years when her own addiction spiraled out of control. Murphy-Ryan is in long-term recovery from a severe alcohol use disorder, and spent months in both inpatient and outpatient addiction treatment.

She also has several loved ones who suffer from mental illness, and she's personally experienced the difficulty of trying to find help for someone in the grips of a psychotic episode.

Most of us have observed someone suffering from psychotic symptoms, and so we share a common image of what it looks like, though it's perhaps stereotypical. Murphy-Ryan conjured up, as an example, the idea of a disheveled-looking man walking down the street, talking to himself and gesturing to the air, seemingly in a world of his own.

"That's only a very small part of what psychosis is and what it means," she said. "So when we see somebody and they are — if somebody is hearing voices, hearing things that, you know, the rest of us are not detecting, we would call that an auditory hallucination. And that's an example of only one type of symptom of psychosis."

Mental health experts divide these symptoms into two types: positive and negative. A hallucination is considered a "positive" symptom — not because it's pleasant, but because it adds something to a person's experience beyond what the rest of us would consider to be the evidence of our senses.

Hallucinations can be auditory, visual, sometimes even physical sensations. Perhaps the most profound symptoms of psychosis come in the form of delusions, when the mind makes connections or creates narratives about the world that are not based in reality. But to someone suffering from them, they are just as real as anything else.

Then there are the negative symptoms. Those are most noticeable in things like disorganization and isolation — things that subtract from someone's ability to function in daily life.

"They can lose interest in things that they used to be very interested in," Murphy-Ryan said. "They may lose their ability to really detect subtle changes in other people's facial expressions. So they lose this kind of social richness of their life. And so the motivation for it and the ability to really pick up on things socially can really disappear."

While positive symptoms are perhaps the most noticeable, Murphy-Ryan explained that negative symptoms can have the larger impact on someone's ability to thrive, even survive. They're at least one way that someone can end up losing their housing, or lack the wherewithal to navigate a way back into housing once unhoused.

How psychosis develops

Psychotic disorders share common symptoms, but the root causes can be diverse and complex. Genetics do play a role, though Murphy-Ryan lamented that there's no single gene that determines whether someone will develop schizophrenia, for example.

"There's hundreds of genes that add a little bit of extra risk of developing, say, a psychotic disorder or mood disorder. And each family has their own kind of complement of it, right?" she said. "And so then you put that in the context of environmental stressors, trauma, early childhood adverse experiences are a known risk factor for having psychotic symptoms or a psychotic disorder."

Drug use can be a major risk factor for psychotic symptoms, both through intoxication and withdrawal from a substance. The big culprits, according to Murphy-Ryan, are stimulants like methamphetamine and mixed amphetamine salts (the latter of which we know best under the brand name Adderall), cannabis and alcohol.

"I think people are often surprised by how much of a link cannabis has with psychosis, particularly with how much attention has been placed on methamphetamine, for example," she said. "But there are some things we know about types of cannabis use that are especially high risk for developing a long-term psychotic disorder, which often gets diagnosed as schizophrenia."

It's particularly an issue with adolescents who are heavy cannabis users, Murphy-Ryan said, who can develop a psychotic disorder earlier or more severely than they would have otherwise. It doesn't happen to everyone, but it can considerably up the odds in the genetic lottery.

"Methamphetamine is similar in that you can get a more immediate or acute psychosis, psychotic symptoms with intoxication," she continued. "And it can also, with prolonged use, contribute to developing a kind of chronic psychotic disorder that looks very similar to schizophrenia — maybe with fewer negative symptoms and more positive symptoms."

Murphy-Ryan stressed that almost anyone can develop psychotic symptoms — although they're more likely to be transitory — in periods of extreme stress or due to another, seemingly-unrelated medical or mental health issue.

Violence and vulnerability

Murphy-Ryan presumes one of the big reasons homeless people turn to stimulants like meth is that it simply isn't safe to be asleep on the streets, particularly for women. That can create something of a vicious cycle when psychotic symptoms are involved — stimulants mixing with lack of sleep and feelings, often justified, of insecurity and paranoia.

"There's been so many times when a patient of mine has declined medication because it makes them too sleepy to defend themselves, even when it helps a lot in the hospital, right?" she said. "And they just cannot take it when they leave because it's not safe. So that's really important. And many people don't feel safe necessarily in shelters either. So it gets complex."

The Seattle doctor is more than a little exasperated with the debate over "housing first" versus "treatment first" models when it comes to addressing homelessness and addiction — they absolutely need to be paired together, she said — but having housing can decrease the risk of psychotic symptoms by providing a sense of security.

Having psychosis, particularly on the streets, can increase someone's risk of becoming a victim of violence, Murphy-Ryan said — people with psychotic disorders are more likely to be the victim of violence than the perpetrator. That said, the psychotic symptoms of delusion and paranoia can result in a level of fear that culminates in acts of aggression.

"They might be very scared and misinterpret what you're trying to do, you may be coming across to them as somebody who is quite dangerous, right?" Murphy-Ryan said. "And so that's really, that is a risk factor for them trying to protect themselves from something that, you know, is not grounded in the reality that we share."

Sometimes the psychotic symptoms can be paired with something like mania or heightened irritability that are more of a risk than the psychosis itself, Murphy-Ryan said — adding an aggressive element to the existing paranoia and fear.

Portland has seen a few high-profile crimes within the last several months where statements made by the suspects suggest that delusional, hallucinatory psychotic symptoms played at least some role.

In December, a woman and her 3-year-old child were waiting at a Northeast Portland MAX station when, suddenly and without provocation, 32-year-old Brianna Workman allegedly shoved the child off the platform and down onto the tracks. Though court documents indicate that Workman refused to participate in an intake assessment, she made statements in a previous assault case indicating a disconnect with reality. Regardless, a mental health assessment in the most recent case determined that she was fit to proceed in court.

At the beginning of January, the historic Portland Korean Church — which sat vacant for years — was spectacularly gutted by fire in an apparent arson. Fire investigators later arrested 27-year-old Nicolette Storer, who told detectives she heard voices saying she would be mutilated if she did not torch the church. Storer indicated that she suffers from schizophrenia and had been using opioids.

Perhaps the most dramatic example happened on the same day as the fire at the Portland Korean Church. Police were called to a MAX platform in Gresham, where they stopped a man who was allegedly in the process of mauling another man's face, having already bitten off the victim's ear.

The suspect, identified as 25-year-old Koryn Kraemer, was once a soccer star at Oberlin College in Ohio. He told investigators that he believed the victim was a robot who was trying to kill him, and he said that police "saved his life" when they arrived to intervene. He also admitted to using cannabis, alcohol and fentanyl prior to the attack. Kraemer's since been found unfit to proceed in court.

All three suspects were unhoused when the alleged crimes happened, and each either admitted to current substance use or, in Workman's case, had prior convictions involving drug possession.

By virtue of the dramatic, inscrutable nature of acts like these, psychosis can seem particularly scary. But, Murphy-Ryan contends, violence is more the exception than the rule — and it tends to be the influence of substances like meth or alcohol that raise the risk of violence, rather than psychosis itself.

"If somebody's having a delusion, they're not always negative. Some people have delusions that are helpful in their lives, and we would definitely not think that that's a risk for violence. Some people have delusions that they have billions of dollars and want to give it to a family member!" she said with a laugh. "I have a family member that currently thinks that, and it's like, 'OK, I'm not gonna send this person to the ER.' This is not a violence risk, right? They may be delusional and they're fine living in the community. So I think we have to keep that in context."

The role of addiction

Though substance abuse can cause some lasting damage to cognitive function and mental health, Murphy-Ryan made clear that even decreasing the amount that someone uses can help address psychotic symptoms, at least when substances are a factor. But addiction can immediately become a barrier to treatment.

"With substance use disorders, your sense of choice and priorities, it gets so separated from your values at your baseline, like before you started using, and it becomes extremely hard to make decisions that even, you know, are in your best interest," she said. "And we really want to support people with that."

Unfortunately, that's an intensive process, and part of the reason why all of this is so difficult. For the best chances of recovery, especially from some combination of homelessness, mental illness and substance use, Murphy-Ryan said that a long-term rehabilitation center is necessary, a place where they can stay for a month or more — something that really isn't available to people without considerable disposable income.

In Oregon, even connecting with a detox center, which usually involves a much shorter-term stay, can be incredibly difficult. Measure 110 was billed as a way to expand Oregon's capacity for drug treatment, but those funds have been able to create outreach more quickly than beds.

"One of the most demoralizing things that I've gone through with my patients is not having a place available to them," Murphy-Ryan said. "You know, they'll come in, they're in the hospital because they're so medically ill related to substance use, and they want help, and we don't have a place where they can go and be away from substances to help support their motivation to decrease or stop their use."

She recalled that when she hit rock bottom with her own addiction and reached out for help, she was able to get into rehab 7 days later. A family member took care of her during that week, staying with her and seeing to her needs.

Family and private insurance paid for Murphy-Ryan's treatment. And after getting that immediate help, she maintains her recovery to this day through a mix of psychotherapy, psychiatric medication management and active involvement in 12-step communities.

"I want that so badly for my patients," Murphy-Ryan said of the addiction treatment services she received. "I mean, many of them don't have that family, and we don't have any services that are gonna fill in that place. I mean ... those beds are so limited. So it's heartbreaking and it's definitely very motivating to work in the field. And I think long-term treatment centers are something that we desperately, desperately need because there is the desire that patients have to go there, and we just don't have the availability."

When addiction clinicians repeatedly run into that wall, one that's a matter of resources rather than the patient's willingness to seek help, Murphy-Ryan believes that it becomes a major contributor to burnout. It's a big part of the reason why workforce shortages have become another barrier for offering mental health and addiction services.

"Psychosis is very complex and the interplay of substance use, trauma, psychosis and housing instability is extremely complex," she said. "We need treatment on demand — like when people are ready, especially with substance use disorders, when people are ready to make a change and want help to have something available to them that's gonna meet their needs is really important and something that's very much missing right now."

Her perspective is borne out by the experience of Oregonians directly dealing with addiction in their lives. Timing is everything, and promptness is in short supply.

But beyond having beds available immediately, there's also the matter of long-term care, even for the people who do manage to get help and eventually beat addiction.

"We're gonna see people with — especially, you know, the folks who survive substance use — who may have had ... oxygen loss in their brain due to overdoses on opioids, fentanyl, and they also have longer-term cognitive damage from methamphetamine," Murphy-Ryan said. "I mean, those people are gonna need a lot of support and we really don't have that set up for them in terms of getting cognitive support, getting assistance, getting re-employed, you know, all of these things. It's really missing."

Understandably, much of the focus at present is on the bleeding edge of the crisis on our streets — on people living unsheltered, actively using drugs and suffering from untreated mental illness. But Murphy-Ryan is looking ahead to what will be needed next, and it's much more than simply getting people into housing.

"To keep from getting demoralized in this field, it's really important for people to spend some time around folks with longer term recovery from psychosis or substance use," she said, "because you realize that people can make immense changes in their life and that people that are, are doing really well and giving a lot to others who may have been looking the same way as a person who's just been readmitted to the hospital for the sixth time in a month, you know — and you just never know which person is gonna be the one to be able to make it. And I think that just gives me a lot of persistence with everybody."

Living with psychosis

There are types of therapy and some medications that can be effective in treating psychotic symptoms, Murphy-Ryan said. For people with psychotic disorders, it can still mean that they're finding ways to live with symptoms long term, even when substance abuse isn't part of the problem.

The UW School of Medicine hosts a training program for therapists specific to helping people with these long-term psychotic symptoms, known as cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis. This type of therapy works to help people experiencing delusions or hallucinations that influence their behavior to make decisions more closely aligned with their values.

"It really honors the fact that not all psychotic symptoms are created equal in terms of whether they're causing suffering or not," Murphy-Ryan said. "And we really just wanna focus on things that are impairing somebody's ability to be in community ... to meet their needs and to have a life that feels fulfilled."

In a manner of speaking, this type of therapy attempts to go with the flow of psychotic symptoms. For someone with delusions that tend to be more grandiose, for example, mental health clinicians using this model might work to get the client involved in helping people — doing something genuinely important.

"It's a way of also, if you have somebody who is in a safe place and really engaged with therapy, sometimes doing this type of therapy can really minimize or even avoid the need for medication, which is always nice because it doesn't have physical side effects," Murphy-Ryan added.

She also expressed optimism about the "clubhouse model," which provides community and opportunities to find dignity through work in a supportive environment.

"If you've had a disorder that causes your cognition to be impaired where you're not able to think in an organized fashion or communicate or speak or, you know, be activated as much, having employment that's gonna work with you if you have a mental health day, right?" Murphy-Ryan said of the model. "If you really can't get there, they're not gonna fire you. They know your case worker. It's very supportive. And that can be really key to building self-esteem and empowerment for folks with a severe mental illness, which schizophrenia is considered, for example, or other psychotic disorders."

Clubhouses aren't precisely common in the Pacific Northwest as of yet, but Portland does have the NorthStar Clubhouse, and there's been a Seattle Clubhouse since 2018.

The important thing, Murphy-Ryan said, is that someone with psychotic symptoms is paired with a clinician who understands psychosis and knows about the different options available. Unfortunately, there remains the chronic shortage of addiction specialists in the U.S., and psychiatrists generally. Having that level of understanding is vital to getting someone help.

"I remember at one point sitting in an ER with a family member of mine who was having a mental health crisis that involved a lot of fairly visible psychotic symptoms and the looks that, you know, we got from other people ... they were kind of scared," she recalled. "And I really loved this person and I felt very defensive. I felt very alienated. It was embarrassing. And I then felt angry that I felt embarrassed. It was just ... I mean, it just brings back a lot just talking about it."

For that reason, Murphy-Ryan said, it can be just as important to have support available for the loved ones of people who suffer from psychotic symptoms. Mental illness wears on everyone it touches, often necessitating a network of care to help even one person get better.

The UW School of Medicine's Psychosis REACH program helps train relatives and friends of people with psychotic symptoms to better care for and relate to them. The half-day course, paired with on-demand training, is now offered fully online.