Salem's drinking water crisis this summer revealed ineffectual communication within the city of Salem, compounding a public health emergency with a public relations disaster, according to a report released Friday.

City officials failed to adequately communicate with their staff and City Council members, didn't provide adequate information to the public when the drinking water advisory was first issued, lacked emergency communications experience in critical staff positions, were unable to send out information quickly in Spanish, and were not prepared to handle the deluge of calls from residents and the news media.

"The city’s communications structure was inadequate to handle public response to the advisory," the report said.

But, the report said the city successfully protected its residents from algal toxins in the water supply. It praised officials for quickly devising a powder activated carbon method to remove cyanotoxins, and for working long hours and canceling vacations to solve the problem.

Salem water crisis timeline: What city officials knew and when

The report also said many of the communication failures that defined the first health advisory were addressed when the city issued a second advisory several days later.

Compiled by The Novak Consulting Group at the request of the city, the report is based on interviews with more than 20 city staff members, council members and external partners, as well as a review of documents and news articles. It cost the city $18,600.

In addition to the communications fiasco, the report noted other shortcomings, including: an inoperable email network to coordinate community response, unusable water tanks that could have been used to distribute drinking water, no response plan in place for high cyanotoxin levels, and a failure to anticipate how significant an advisory would impact the public.

The intent of the report, it said, is to identify ways to help the city improve, not place blame.

City officials agreed with the report's findings and concluded it was an objective and fair assessment of how staff conducted their response to the drinking water crisis.

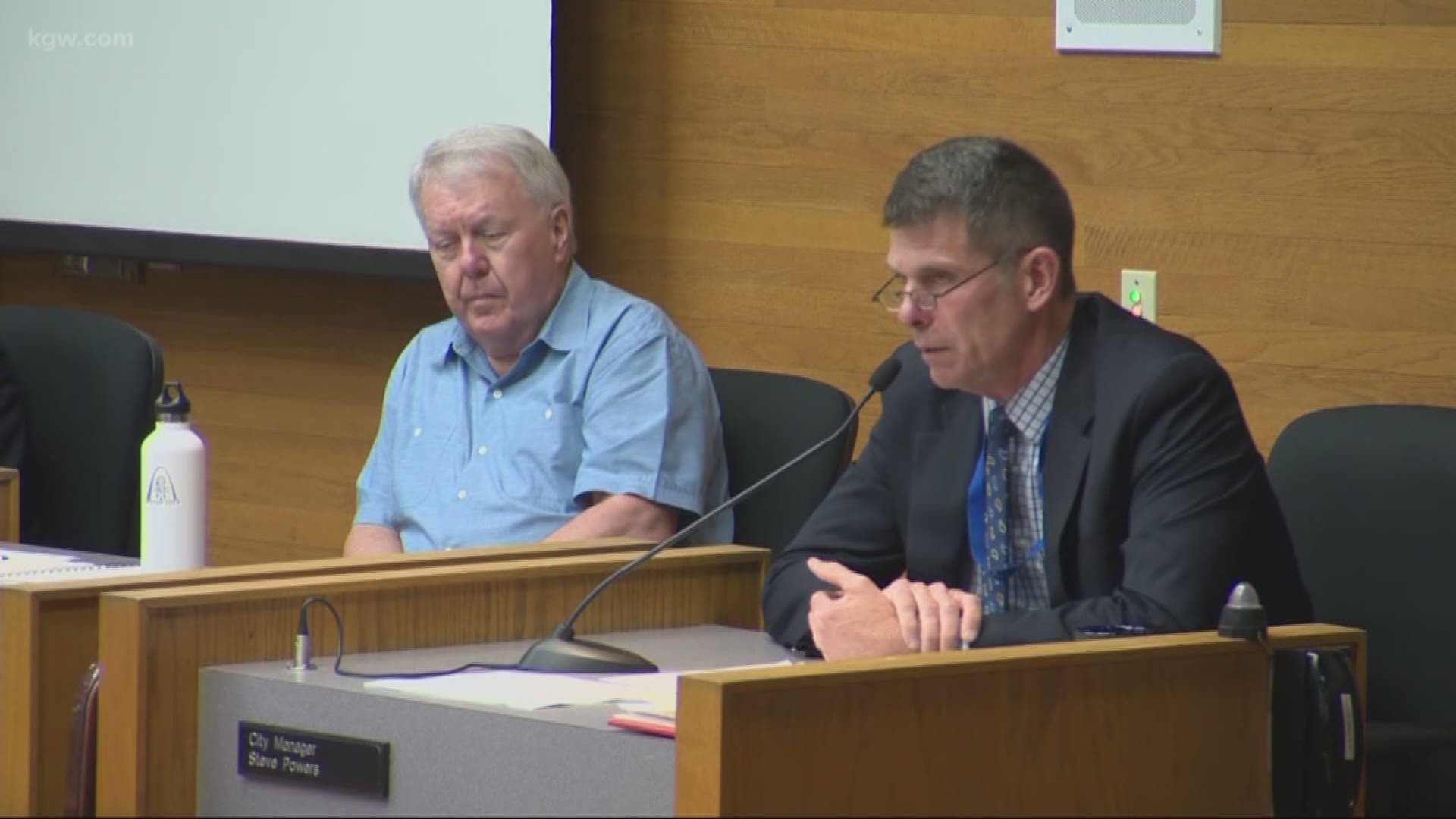

In an interview Friday, City Manager Steve Powers, Public Works Director Peter Fernandez and spokesman Kenny Larson acknowledged there were many missteps after cyanotoxins were discovered in the city's water supply.

They continue to look at this as a learning opportunity. Powers said he won't be asking for any resignations in light of the report.

“Any public organization should be committed to continuous learning, to be transparent and share what went well and what didn’t go well to help prepare and improve for the next event,” Powers said. “That’s extremely true with emergency management.”

In a direct response, the city is looking at increasing the number of people responsible for communications. Powers couldn't say definitively that more communications professionals would be hired, only that it would be an aspect of budget conversations later this year.

Several people are referenced in the report as saying the city tends to emphasize technical skills over communication.

"We've been more technically oriented. 'Hey, let's just get the work done.' Really what we've learned from this, and have really internalized, is that communication has to be an important piece," Fernandez said.

The crisis began May 25 when Salem Public Works staff became aware of cyanotoxins in the drinking water above EPA health advisory levels for vulnerable populations. At potential risk were young children, pets, pregnant or nursing mothers, and people with kidney or liver disease or impaired immune systems.

The first drinking water advisory was issued May 29, then lifted on June 2 after tests showed lower cyanotoxin levels for several consecutive days. A second advisory was placed June 6 after cyanotoxins once again spiked above safe levels for vulnerable populations. It lasted until July 3.

Salem Mayor Chuck Bennett said he would give city officials a "D" or an "F" grade for their immediate response to the event, but he was more impressed with them as it unfolded.

Bennett said city officials are doing the right thing by taking an honest look at their performance.

The city of Salem wasn't the only organization highlighted for an insufficient response to the crisis.

According to the report, multiple city and Marion County officials said Oregon Health Authority was unable to give them sufficient guidance on how to respond to heightened levels of cyanotoxins. Such direction from the state's public health authority would have been helpful, they said.

OHA staff, meanwhile, said they felt hamstrung by the lack of established rules dictating what an appropriate response looks like. Cyanotoxins are an unregulated contaminate for the EPA and an emerging problem for water systems nationwide.

Despite Salem having voluntarily tested for the toxins since 2011, "there was no plan of action in place for the City to follow as a response to positive testing," the report noted. Throughout the crisis, city officials touted this voluntary testing as the only reason cyanotoxins were identified in the water supply.

No city in Oregon had ever responded to cyanotoxin levels above the EPA health advisory.

The report also noted a series of other preparedness failures.

First, at the time of the initial advisory, the city had in its possession two water tank vehicles that could have been used to transport water to residents, but their interiors were rusted and "unfit" to carry drinking water.

One of the tanks was just a year old and had its lid left open in the rain. The other was not on a maintenance schedule and had deteriorated over time.

Fernandez said those tankers have already been refurbished.

"Our thought of those tankers in the past was that we would be providing water to others," Fernandez said. "They weren't really there to provide water to ourselves, but we've now learned the lesson."

The city had also established an email list for a community emergency response team, with 600 volunteers listed, but that was "nearly unusable," the report said. When an email to the group was sent out, the "vast majority" came back as un-deliverable.

The report also noted that only 8 percent of households had water stored in case of emergency, and 15 percent of residents were signed up for the city-wide emergency alert system.

Salem has now signed up for the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System, used across the country. These alerts do not require registration.

“We learned some hard, difficult lessons,” Larson said.

Reporter Jonathan Bach contributed to this report.

Contact the reporter at cradnovich@statesmanjournal.com or 503-399-6864, or follow him on Twitter at @CDRadnovich