WILSONVILLE, Ore. — Mothers incarcerated at Oregon’s only women’s prison may soon lose out on a crucial resource in helping them maintain strong connections with their kids.

Directors of the Family Preservation Project, or FPP, worry if a bill aimed at renewing the program’s state funding doesn’t get a vote before the legislative session ends next week, the worst impacts will be felt by those children.

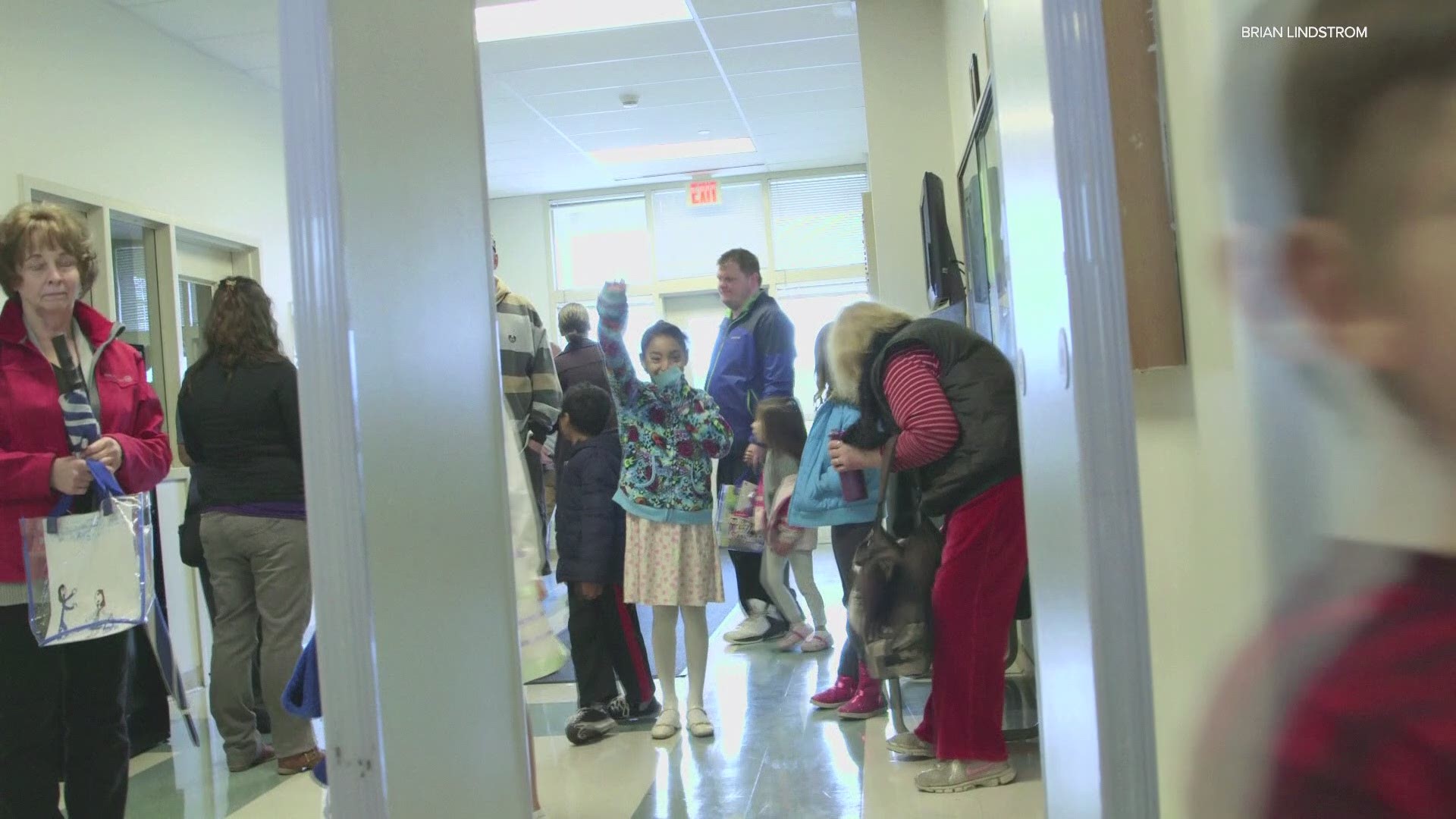

Directors say FPP helps facilitate regular family visits by providing caregivers with gas cards and other financial assistance so that kids can get to the Coffee Creek Correctional Facility in Wilsonville.

If that caregiver has a felony on their record, and therefore can’t enter the prison, FPP clinicians take the children inside. It also helps moms stay in touch with their kids on the outside, as well as connect with their teachers and coaches. Perhaps most importantly, directors said, FPP ensures moms and kids have time to read, draw and hug during visits.

Without FPP, said Vanessa Sherrod, her visits with her kids would have been cold and sterile. At best, they might have been able to eat a meal together.

“I'm looking at my three kids, and I know that that program meant so much to me when I was inside,” Sherrod said in an interview Monday. “[Through FPP], I helped to build a village from inside the prison system that would support my kids.”

Convicted on multiple counts of theft, Sherrod spent more than four years inside Coffee Creek. KGW covered the buildup to her release in a three-part, Emmy-winning series LIFE Inside, which aired in February 2020.

Sherrod was released in the winter of 2019. The mom of three has since gotten her associate’s degree in social work and a full-time job with the YWCA of Greater Portland, which runs FPP.

Lately, a main facet of Sherrod’s job includes advocating for Senate Bill 720. If passed, it would maintain the past state funding levels for FPP at $325,000 a year for the next seven years. It would also cover the cost of research on the long-term impacts of the program, allowing directors to provide lawmakers with hard data on the benefits of helping moms remain an important part of their kids’ lives from inside prison.

Studies show children of incarcerated parents often suffer from psychological and emotional problems, trouble in school and they're six times more likely to become incarcerated themselves. FPP directors believe their program is actively combatting those trends, but right now, all they have is anecdotal evidence.

The need has been even greater during the COVID pandemic, said Sherrod. Visitors have been barred from Oregon’s prisons, forcing the Family Preservation Project to shift to remote communication.

“There was like 224 moms that we helped with phone calls, video visits,” she said. “There was nobody to pay for those video visits. There was no one to pay for those phone calls or pay for the amount of letters to go out to their kids or to come back to the parents. So we had that support, and we were able to do that, but that's not always going to be the case.”

A spokesperson for the Department of Corrections told KGW via email in-person visits will resume Monday.

FPP founder and director Jessica Katz hopes state lawmakers are able to push SB 720 out of its apparent holding pattern in time for a vote next week. Right now, it’s stuck in the legislature’s Ways and Means committee. Katz is afraid lawmakers are too swamped with the major systemic issues of 2020: dispersing federal COVID aid, Oregon's housing emergency, wildfire relief, police reform and others.

The lack of bandwidth in the legislature, Katz fears, is putting the Family Preservation Project on life support.

“I think investing in the right staff with the right training is critical. The state's investment allows for us to do that,” Katz said, adding a full staff includes three full-time licensed clinicians, plus a fourth part-time one and three interns. “So much of what we're looking at interrupting are these intergenerational cycles of pain and suffering, and you're doing it inside of an environment that induces trauma.”

This isn’t FPP’s first battle with maintaining state funding levels. The last several attempts to get bills like SB 720 passed have been thwarted, not by opposition, but by GOP walkouts over the controversial carbon emissions bill known as "cap-and-trade." Walkouts robbed lawmakers of the quorum needed to vote on cap-and-trade, along with dozens of others.

Bills tied to FPP’s funding have died multiple times. In the interim, the YWCA has been picking up the tab. Now, they’re out of money and time.

Lawmakers have told them, if the bill dies, they’ll try to get one year of funding included in the general state budget. But after so many walkouts, Katz and Sherrod want the security that seven years of funding would bring.

“It’s been crazy to think that thus far we haven't got it done, but it has to get done this year,” Sherrod said. “I mean, it has to.”

Since the public, including lobbyists, are still barred from Oregon’s state capitol, advocating for SB 720 has come down to phone calls and Zoom meetings. Sherrod’s secret weapon is, and has been for years, a half hour documentary on FPP called “Mothering Inside”. Produced by local filmmaker Brian Lindstrom, it shows moms and kids having those intimate family visits and discussing how difficult the time apart has been.

Lindstrom, husband to “Wild” author Cheryl Strayed, shot the documentary in 2014 and released it a year later.

“As a parent, when I was filming this, I mean, I would have to sometimes bite my lip just because I couldn't help but put myself and my kids in that position and think like ‘Wow, what would that be like?’” he said in an interview Monday. “[The moms and kids] would just be talking about what happened at school or was there a TV show they liked or just, you know, the mundane things. But the fact that they got to do that and they could be touching each other, they could be eating, they could be reading together. None of that stuff can happen on your typical prison visit where there's plexiglass between them.”

If there any further questions about SB 720, Sherrod tells them about her kids. All three, she boasted, are A and B students.

Her 14-year-old Roxanna Frias had a question for lawmakers.

“I would just ask them like ‘How would you feel if someone wasn't fighting for you to be able to see your mom more often and be able to enjoy experiences you wouldn't get if your parent was incarcerated?” she said. “I wish I could just talk to them.”