PORTLAND, Ore. — For many Native Americans, the topic of Indian boarding schools remains a dark, hidden part of history that too few people know about.

Advocates say the conversation around how Indigenous people have historically been treated in the United States should have started a long time ago. With last Monday being Indigenous Peoples’ Day and November being National Native American Heritage Month, topics like this are especially timely.

A warning, this article contains some graphic descriptions of abuse.

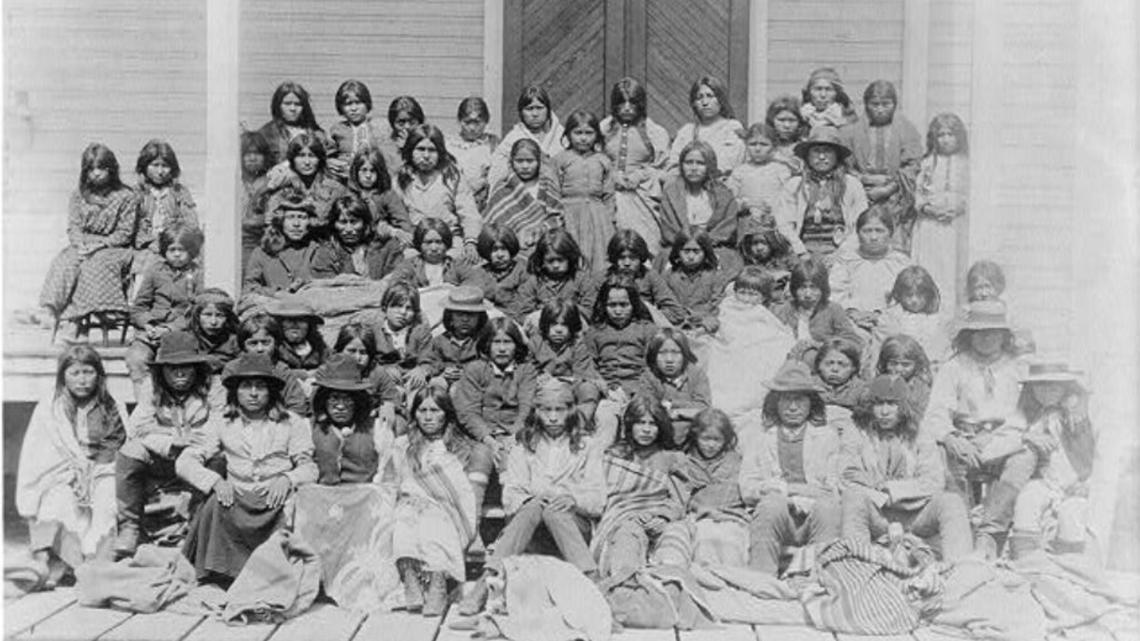

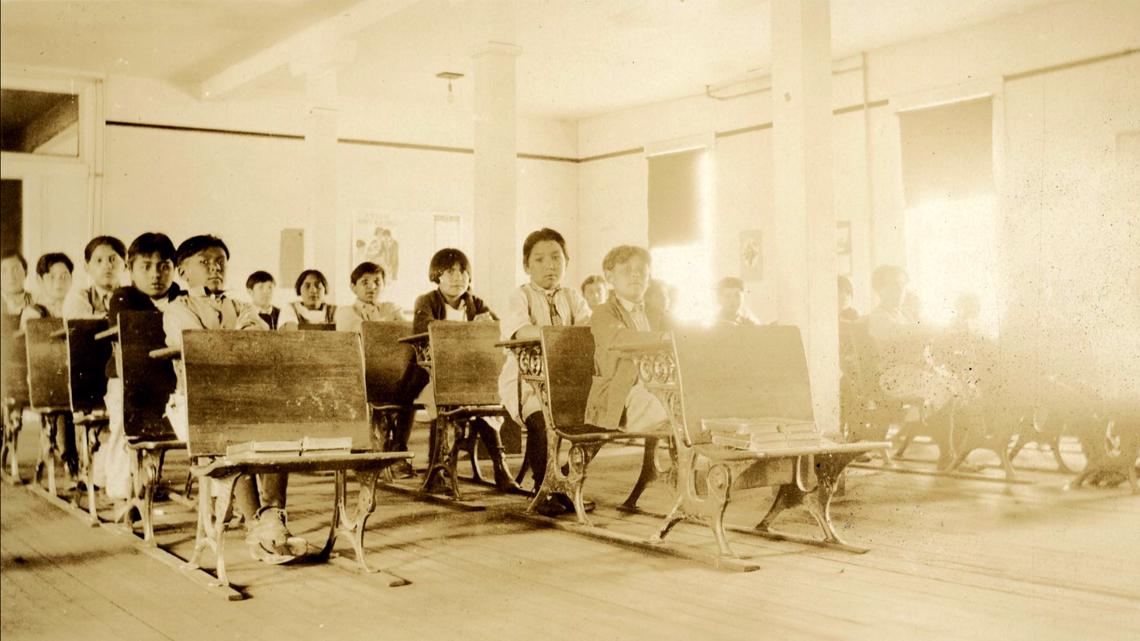

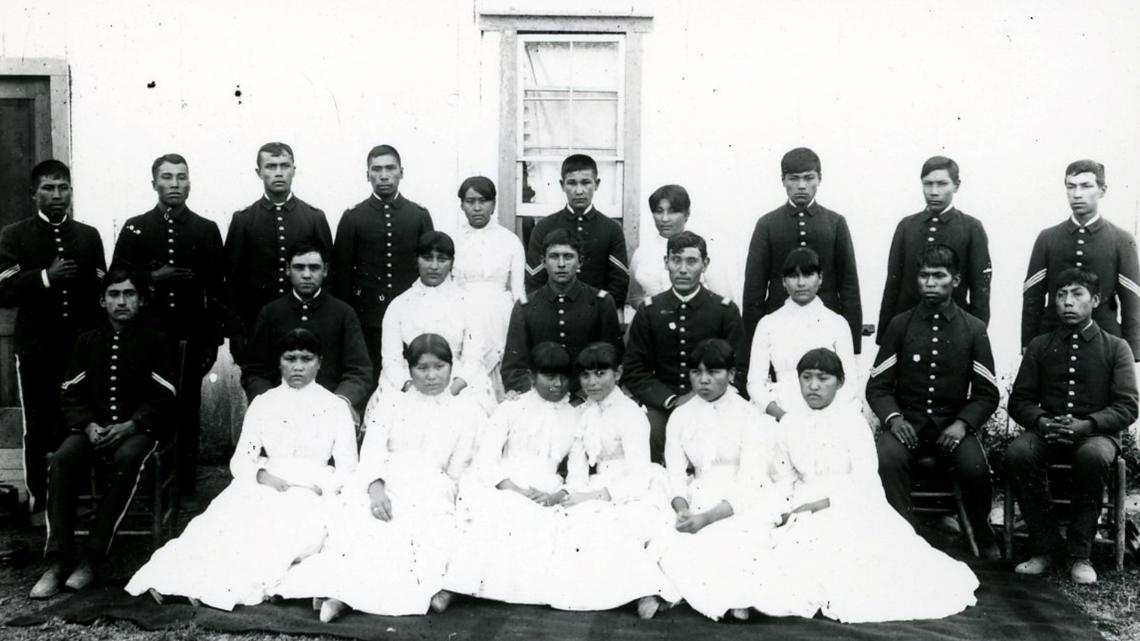

In the late 1800s, what are known as Indian boarding schools could be found across the country and in the Pacific Northwest. Indigenous children were taken to the schools to learn trade skills, religion and English.

In 1880, one was established in Forest Grove. It was called the Forest Grove Indian Industrial and Training School. Native children from all over the region were brought there. Five years later, after a fire destroyed one of the buildings, the school moved to where Chemawa Indian School is today just north of Salem.

The history of Indian boarding schools is a traumatic one that’s well known among many tribes.

“Sul Ka Dub is my Indian name. My Christian name is Freddie Lane. I'm Lhaq'temish. Lummi is the reservation. Lhaq'temish are the people of the Pacific Northwest,” said Freddie Lane as he introduced himself.

Tawna Sanchez, the director of family services at Native American Youth and Family Center and the state representative for House District 43 as well as David Lewis, a member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde who is also a faculty member at Oregon State University, also spent time talking about the history of boarding schools.

“There were over 357 documented boarding schools across this country,” said Sanchez.

It all started with laws and treaties.

“Back in the early 1800s […] There was this thing called the Civilization Fund Act, which essentially was, you know, a way to try to civilize the American Indian populations,” said Sanchez.

The traumatic history of boarding schools

After that, the stories and trauma associated with the boarding schools that arose have been passed down through generations by oral tradition. Many have called what happened "cultural genocide." It started with the rounding up of Indigenous kids.

“Some kids would go in at the age of 6 and would never be seen again,” said Lewis.

“I have listened to stories from the elders who talked about being on the high point of the river, where their parents were down there fishing, and having this police car come and just take them all away and never seeing their parents again,” Sanchez said.

“They were forced to speak English. They were forced to learn Christianity,” she said.

Sanchez added that it’s because of boarding schools that so many tribes are trying to retrieve their language and rekindle their culture, because much of it was lost in the schools.

“You were beaten, in some cases for […] speaking your language. The mentality was, ‘kill the Indian save the man.’ That was the government's policy,” explained Lane.

He said he often encounters people who don’t know about Indian boarding schools that were operating in the U.S. and Oregon.

“It’s something that Uncle Sam would rather not talk about,” Lane said.

Sanchez said many of the children who went into boarding schools never made it home. She pointed to a burial ground near the Chemawa Indian School. A metal gate at the entrance of the cemetery indicates it was established in 1886.

According to Pacific University, researchers have documented 275 students and 30 other non-students buried at the Chemawa School Cemetery. While generally, sickness did spread in the boarding schools, those in the Indigenous community say it wasn't just disease that killed students.

"The abuse that happened in those schools was immense."

“We're talking about, you know, basically murder on the part of teachers in many schools,” said Lewis.

“The abuse that happened in those schools was immense,” Sanchez said. “There was sexual abuse there that's well documented.”

Lane said he recalls a heavy conversation he had with a 75-year-old tribal chief who went to a boarding school in Canada.

“I’ve never seen a chief cry. I wouldn't believe it if he didn't tell me, how the priests up in Canada, they would rape the children. And the nuns would hide the pregnancy […] Those nuns who believed in god, in the name of god, they threw those children in the furnace. They were born and then they burned,” said Lane.

He said in some cases Native American women were sterilized at boarding schools. To this day, the extent of abuse is difficult to quantify.

"We're not willing to look sometimes at the history here, right here in the United States. It's really quite sad,” Sanchez said.

All that trauma has been passed down through generations.

“For so many families, this was just a huge trauma that passed down generationally to people. That hurt and that damage that happened to them, just doesn't go away,” said Sanchez.

She said over the years, it’s had a trickle-down effect.

“We're still one of the, you know, highest levels of poverty populations in the entire country. We're still struggling with basic needs in some areas. Warm Springs is still struggling with water. The infrastructure around their water systems is not there,” Sanchez said.

Chemawa Indian School still in operation but in a different way

Sanchez said Chemawa Indian School is very different today than when it was in the late-1800s and early-1900s.

“In some instances, it’s an opportunity for kiddos who don’t fit in their regular school systems,” said Sanchez.

In addition, she said culture is much more emphasized these days and the school is far more culturally engaged.

Lane and his father both attended Chemawa and both had a positive experience. Lane said what he learned at Chemewa was life changing, setting the foundation for his success later in life.

Lewis said residential schools, like Chemawa, also helped create what many know as the powwow.

“Different Native populations from different tribes were exposed to each other and, you know, new traditions arose like the powwow and that sort of thing, which probably allowed them to feel connected to others, even though they're not from the same tribe,” said Lewis.

Beginning to heal

Another positive, Sanchez said, comes from action taken at the national level by Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve in a cabinet position as the U.S. Secretary of the Interior.

“[She] has initiated a federal Indian boarding school initiative that will actually do some research into the boarding schools here in the United States,” said Sanchez.

That may be how the healing starts and how we move forward together, however painful it may be.

“We really just have to own that these things happened and that the audacity of us to try to forget that or pretend it didn’t happen, I think that’s wrong. Acknowledgement of the damage we’ve done to Native populations has to happen. And an apology, just won't do it,” Sanchez said.

“The country was, you know, essentially built on damaging other people, other humans.”

KGW reached out to Chemawa for a comment, but without approval from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), they weren’t able to speak with us. While the BIA did not give approval, the deputy press secretary sent a statement detailing the work that the U.S. Department of the Interior will be doing to investigate “the loss of human life and the lasting consequences of residential Indian boarding schools.”

Deputy press secretary Giovanni Rocco said not only will the department be gathering feedback from Indigenous communities through December; it’ll also continue to compile decades of files to improve its records and work to protect potential burial sites.